The essential distinction between preaching and teaching in the New Testament is the difference between scuba diving, on the one hand, and snorkeling, on the other. In snorkeling, one observes the pristine beauty of the marine world with its variety of ichthyological life, but with scuba one discovers intricacies unobservable from the surface. Snorkeling has its dangers (boats, jet skis, diving swimmers, and so on), while the lurking dangers of the deep are more subtle (lion fish, sea snakes, and a condition called “narcosis,” in which a diver becomes so drunk that he may, with great confidence, remove his mask and offer it to a passing grouper).

Preaching is more like snorkeling, and teaching is more like scuba. Preaching most often involves more people, who are interacting initially with faith on the surface of life. Teaching involves fewer people — those more serious about faith — who have a desire for a closer look at the mysteries of the depths and the intricacies of God’s Word. Some imagine that preaching involves greater passion than teaching. While this may often be the case, such a conclusion is neither essential nor constant. Most can remember intolerably boring sermons as well as electrifying sessions with an omnicompetent teacher.

The New Testament vocabulary for teaching and preaching is instructive. Preaching employs two words. Sometimes the preaching is content-specific. The Gospel is being preached, and the word used is euaggelizomai, meaning “proclaim the good news.” The history of the word among the Greeks extends back to Aristophanes (436-386 B.C.), and while used in a variety of ways, primarily it was used to announce a great victory. Sometimes this was conveyed in book form, but usually as a verbal announcement to an assembly of people. Always in the New Testament, the word is used in the sense of proclaiming the saving truth of Jesus the Savior. However, both the synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John carry that title now.

The second word employed is kērussō. The kērux (nominal form) was well known in the Greco-Roman world. The “herald” was a messenger. Usually possessed of a strong vocal instrument, in the vigor of health, he had to travel distances in order to announce this critical news. Without radio, television, computer, or public address system, the assignment of this messenger was demanding and critically essential.

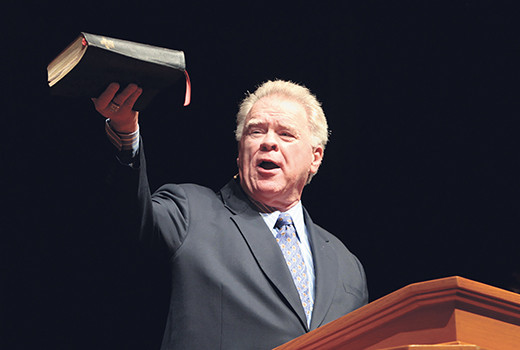

The preacher is a kērux. His task is to proclaim the Word of God, openly and before gathered assemblies of men and women. This oral activity comes with a promised blessing of God and an anointing of God for the task. The overwhelming majority of these messengers were pastors. Some were evangelists, and some, like Philip, were evidently lay people. A pastoral calling was not mandatory, but, rather, the anointing of God — the presence and power of the Holy Spirit — was essential. First Corinthians 1:21 suggests the genius of our God in choosing the foolishness of that which is preached (kērugmatos, in the Greek) to save many.

There are other words for preaching in the New Testament, but these two are primary. With these words, we may define preaching as the art of a Spirit-anointed man of God proclaiming publicly the Word of God and especially the message of the saving Gospel of Jesus the Christ. Absent the anointing of the Holy Spirit, the herald may be preaching, but it is not Christian preaching.

When the subject turns to teaching, an appropriate observation is that the distinction between preaching and teaching is only partly sustainable because all genuinely good preaching is also good teaching. A text-driven sermon — the only kind worthy of a Christian preacher — will be a sermon designed not only to inspire and evoke a decision from the listener but also to explain carefully the text in view.

Nevertheless, the Greek word didaskō also has a life of its own in the church of the Lord. In pre-New Testament Greek, the word was widely used. Originally, it referenced an activity involving at least two people — one anticipating instruction and one comprehending the content of the instruction to be imparted. Though not always the case, teaching generally involves a smaller convocation coupled with the opportunity to dig into the text of Scripture more deeply than may be the case in preaching. The teacher, together with a smaller cadre of disciples, has the opportunity to probe the meaning of text or subject in what is generally a more relaxed atmosphere.

A word needs also to be said about interpretation. As Jesus walked with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, “beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, He interpreted for them the things concerning Himself in all the Scriptures” (Luke 24:27). The word “interpreted” is the Greek word diermēneuō — which is ultimately derived from Hermes, the messenger of the gods. In the Greek pantheon, Hermes was to interpret the gods to other capricious gods and men. From this word is derived “hermeneutics,” or the science of interpretation. Both teachers and preachers employ hermeneutics.

This leads to a final avowal. In Acts 28:30-31, the history of the early church concludes that Paul continued both preaching and teaching for all who assembled before him. The text clearly recognizes two distinct activities. However, the similarity of the two endeavors is also apparent. Paul was preacher and teacher. So may we all be.

— Paige Patterson is president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas.

Pingback: » Shall We Preach, or Shall We Teach? Theological Matters - 2014