Because of continuing interest in Calvinism and its influence in South Carolina Baptist life, The Baptist Courier ran a five-part series on Calvinism beginning in November, 2000. Many readers contacted us with requests for copies, so we have republished the series here in its entirety.

Loyd Melton

Loyd MeltonThe series was written by Loyd Melton, a Southern Baptist minister and educator who has written curriculum materials and freelance articles for Baptist publications for more than 25 years. He wrote the article on predestination for the Mercer Dictionary of the Bible.

Melton is professor of New Testament and associate dean at Erskine Seminary, where he has taught for the last 23 years. ?

He is a native of South Carolina and was educated at Presbyterian College (B.A.), Erskine Theological Seminary (M.Div.), and he received a Ph.D. in New Testament studies at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He also did further graduate work at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, Ohio. ?Melton has taught at Campbell University and the University of South Carolina.

He has been a pastor of Baptist churches in South Carolina and Kentucky since 1968.

Click on a topic below to go quickly to that subject.

Calvinism and the Human Condition

Calvinism and the Doctrine of Election

Martin Luther posts his “Ninety-Five Theses” on the door of the castle church in Wittenburg, Germany.

Martin Luther posts his “Ninety-Five Theses” on the door of the castle church in Wittenburg, Germany.In many ways, human history was changed on Oct. 31, 1517. It was on this day that Martin Luther posted his Ninety-five Theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenburg, Germany. Luther protested the abuses of the medieval Roman Catholic Church. In particular, the church had made salvation something which could be obtained by human effort and even something which could be purchased. The church, under the control of the Pope, had become the treasury of God’s grace. It could dole out that grace to whomever it wished.

What had been lost in all of this, Luther discovered, was the recognition that God alone was the source of grace. Furthermore, grace could be experienced individually as one acknowledged and repented of his or her sin. Luther’s discovery was life-changing for him and ultimately would change the course of human history. ?

Luther’s intention was to reform the medieval church. His Ninety-five Theses were to be talking points with the Pope. Little did he realize that his actions would evoke such hostile responses from the church he loved. Even less did he realize that they would bring about radical religious, social, political, and economic changes. The fires of reformation which Luther kindled in Germany spread wildly throughout Europe. ?

Although many leaders emerged from the Reformation, the greatest thinker was John Calvin (1509-1564). Calvin grew up in Paris, studied law, and was firmly entrenched in the humanism of the day. Sometime between 1532 and 1534, he experienced a sudden conversion to Christianity. Soon, he found himself sympathetic to the Reformation. He and other Protestants were persecuted in France. He fled to Switzerland. ?

John Calvin as a young man.

John Calvin as a young man.In 1536, he published the Institutes of the Christian Religion, which was prefaced with a letter to the king of France. Calvin sought to defend Protestant believers against the slanders which were being lodged against them. Calvin further expanded his thinking through later editions of the Institutes until the last one appeared in 1559. ?

Although Calvin wrote many other works, his understanding of the Christian faith is most clearly and concisely set out in the Institutes. He was a disciplined and systematic thinker. His Institutes became the systematic theology of the Reformation. Luther was creative in his thinking, but Calvin was ordered in his.

It is helpful to ask at this point: What is central in Calvin’s thinking? While some would say election, predestination, total depravity, the centrality of scripture, or the like, all of these seem to arise from a larger theme. Central to Calvin’s theology is the sovereignty of God. God is always God, and human destiny (especially salvation) is first and last in His hands and under His control. ?

The medieval church had lost its way. Salvation was granted by the church. One’s salvation was dependent upon good works and merit that could be accumulated or granted. Salvation was understood to be purely for the purpose of going to heaven after death. It had little to do with this life and certainly had no impact on the society in which one lived. ?

In short, the medieval church placed people in bondage. The church itself was bound in its own thinking. Neither Luther nor Calvin believed that they were creating something new. Instead, they saw themselves returning to the radical power of the gospel as they discovered it in the writings of Paul. For Paul, belief in Jesus sets one free not only from the fear of judgment and death. It also liberates one to live as a new creature in this world and empowers one to seek to transform this world so that it, too, reflects the sovereignty of God and glorifies Him. ?

Calvin’s theology was deeply experiential and not primarily intellectual. God’s sovereignty in human affairs was not some fatalism that led to resignation in life. It was the joyful acknowledgement that God created human beings for Himself. Life’s chief purpose and highest joy were to glorify God. This was possible because of the sheer joy created when one came to experience salvation purely as God’s gift. ?

No thought of Calvin has been debated as widely as his doctrine of election. Yet, election was for the purpose of assuring, encouraging, and empowering believers. In the Institutes, election is a part of Calvin’s discussion of God’s grace. For Calvin, salvation is always a gift of God that comes through faith. Election liberates one from the frustration and failure of trying to earn his or her salvation and from the deception of humanism, which maintains that salvation is not needed. Election empowers one to live redemptively in a fallen world and sets one free to change it. ?

The latter point is important in understanding Calvin. He believed that God’s sovereignty is to be manifest in human society. He sought to make Geneva, Switzerland, into a Christian community which was shaped, and whose life was ordered, by the claims of the gospel. Calvin’s understanding of the Christian experience of salvation was as dynamic and fresh as Luther’s, whose own life was dramatically changed by his discovery of grace. ?

Calvin’s theology became central as the Reformation spread from Germany, France, and Switzerland to other places. As is often the case, some of the freshness of his thinking became stale and some of its power blunted in the Calvinism that would follow. Calvinism is the system of theology which grew out of Calvin’s thinking. It centered in Calvin’s major doctrines but went beyond them in significant ways. ?

The theology of Calvin met immediate opposition. Obviously, it was opposed by the Catholic Church. Anabaptists rejected his belief in infant baptism. For them, such a practice was a sign that the Reformation had not gone far enough, since Reformers were retaining a practice from the medieval church. Furthermore, Anabaptists argued that only believers’ baptism can be justified from the New Testament. Calvin’s thinking was also opposed by the humanists of his day, who argued that his depiction of the human condition was far too pessimistic. ?

The effect of the challenges to Calvin’s theology was that often those who defended it became more rigorous and unbending than Calvin himself. In the Calvinism that developed, some of the freshness and joy of Calvin’s rediscovery of grace was replaced with rigor, dogmatism, and even arrogance and pride. ?

Jacobus Arminius

Jacobus ArminiusPerhaps the most fierce debate over Calvinism came from Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609) and his followers. This debate will be considered in more detail in a later article. Arminius argued that Calvin’s doctrine of election took away human responsibility and made human beings little more than puppets. Calvinists responded with an even more rigorous doctrine of election. Some of these responses made election into little more than blind fatalism. The debate continues until this day.

The debates over election illustrate the need to distinguish at times Calvinism from Calvin. Calvin’s doctrine of election was never seen by him as fatalism. It was an acknowledgement that God was God, and human beings, because of their broken condition, could never merit salvation. Election for Calvin was the source of confidence and hope for believers that their salvation rested with God alone and was real because of His faithfulness to His promises. This confidence not only gave one hope for heaven, but also empowered one to live a transformed life and to seek to transform society.

John Calvin and the Calvinism that later would develop, prompted diverse reactions from different quarters of the church. Roman Catholics argued that such thinking would produce utter anarchy in the church. Anabaptists saw it as too little change. ?

Perhaps the point of Calvinism that has created the least amount of controversy has been Calvin’s view of the human condition. He discusses the human predicament in Book 2 of the Institutes of the Christian Religion. This section of the Institutes deals with how we come to know God in Christ.. For Calvin, the greatness of God’s gift of salvation can only be seen when one ponders the plight of humanity without God. He says, “We are so vitiated and perverted in every part of our nature that by this great corruption we stand justly condemned and convicted before God, to whom nothing is acceptable but righteousness, innocence, and purity” (Institutes, Book 2, Chapter 1, Section 8). ?

Before discussing the meaning of Calvin’s words, it is important to note two things about the historical context in which they were spoken. First, Calvin wrote in the context of the medieval church, which had made salvation a possession of the church. Thus, the church could grant or withhold it. The effect was that salvation was cheapened. For many, it was little more than a “fire insurance policy.” ?

Generally speaking, there is a close correspondence between one’s view of salvation and one’s view of human nature. Many in the medieval church who did not take salvation seriously also did not take sin seriously. Sin could easily be atoned for by participating in the rituals of the church. ?

The second aspect of Calvin’s context was the humanism of his day. Before his Christian experience, Calvin himself had been trained as a humanist. Humanism maintains that people are not all that bad. Human nature is noble and essentially good. Bad behavior can be changed by education. ?

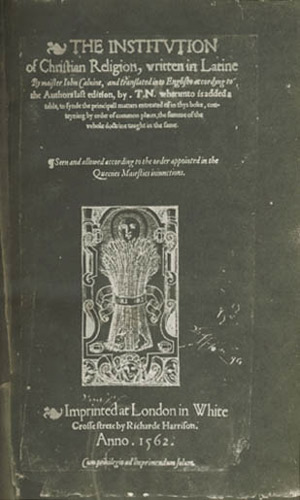

Calvin’s “Institutes of the Christian Religion”

Calvin’s “Institutes of the Christian Religion”Calvin’s purpose in discussing the human condition in Book 2 of the Institutes is to set forth the need for salvation. Interestingly enough, he follows the same logic and order as does Paul in Romans 1-3. As a matter of fact, he bases most of his discussion on Paul’s, it may be helpful to summarize. ?

Man was created to know God and to know himself.?Calvin understands the early chapters of Genesis to show that Adam and Eve had all they needed in the garden. Their relationship with God was pure and harmonious. This peace with God affected all other aspects of their existence. The relationship between Adam and Eve was fulfilling and harmonious. Their relationship with their work and with the created order was peaceful and satisfying. Man possessed clear self-understanding. This means that Adam and Eve understood their proper relationship with God. Their lives were sustained by utter dependence on Him, putting them at peace with their world. ?

Sin entered human experience as man sought to be master of his own life. Calvin calls Adam’s fall his “desertion” (Institutes, Book 2, Chapter 2, Section 4). Adam and Eve turned away from God and from life. The serpent’s temptation was for Adam and Eve to live as gods, determining their own fate, living in subjection to no one. Adam deserted God as Lord and chose to go his own way. Clearly, the serpent’s line was a lie because it promised freedom but delivered only bondage. The original sin was direct disobedience of God’s single command. Adam’s act was based on a lie. This disobedience came about to feed man’s ambition. For Calvin, “if ambition had not raised man higher than was meet and right, he could have remained in his original state” (Institutes, Book 2, Chapter 2, Section 4). ?

The immediate consequence of sin was estrangement. When Adam sought to be his own god, his fellowship with God was broken. He sought to hide from God rather than rejoice in His presence. Peace with God was replaced by fear and dread. The clear understanding of man’s place in God’s world had vanished. ?

Man became estranged in his relationship with himself. He no longer knew who he was. Life now became filled with fear, anxiety and frustration. This estrangement poisoned his relationship with Eve. Peace now was replaced by conflict, trust by doubt. It is significant that resentment and hostility characterize the relationship between Cain and Abel until a tragic murder took place in the first family. ?

Even man’s relationship with nature became estranged. Meaningful work became replaced with burdensome toil. The harmonious earth was infested with thorns and thistles, and the soil no longer freely gave up its fruit. The earth was still God’s gift and would still produce what man needed to live, but now it would be obtained only through struggle and heartache. ?

The devastating results of sin affect every aspect of our being. Our minds, bodies, spirits, and hearts are all infected with this incurable disease. Calvin says, “Paul removes all doubt when he teaches that corruption subsists not in one part only, but that none of the soul remains pure or untouched by this mortal disease” (Institutes, Book II, Chapter 1, Section 9). ?

Adam’s sin has affected all future generations. Adam could not contain his disease within himself any more than he could limit its disastrous consequences. The human condition became irretrievably broken in him. This brokenness was passed down to Adam’s descendants. Calvin calls this “original sin.” He argues that when Adam sinned, “He consigned his race to ruin by his rebellion when he perverted the whole order of nature in heaven and on earth” (Institutes, Book 2, Chapter 1, Section 5). ?

Just as certain physical characteristics are inherited, so is our sinful nature. For Calvin, however, there is a difference. We cannot avoid the responsibility for our sin by blaming Adam. We have inherited our sinful nature from him, but we willingly do the same things Adam did. We like our Adamic nature. We believe the same lie he did, are guilty of the same self-sufficiency he was, are characterized by the same arrogance, and attempt to cover ourselves with the same self-justification. ?

Calvin’s view of original sin was the same as that of Augustine. He, like Augustine, argued against Pelagius, who maintained that we do not inherit a sinful nature. We simply imitate Adam’s sin.

Most evangelicals are at home with Calvin’s assessment of the human condition. One wonders, however, if we really take it that seriously. In the name of making the gospel relevant to modern people today, how many evangelicals preach a “warmed-over self-help” in place of the scandal of the cross? In the name of defending the truth, how many evangelicals equate their own understanding of truth with God’s truth itself? Are not these but two examples of an utter denial of the seriousness of our human condition? ?

No part of Calvin’s thinking has been any more controversial than election. This article will attempt to explain the meaning of election. The final article in this series will deal with biblical texts which seem to support Calvin’s view of election, as well as those which seem to question it. Some attention will then be given to Baptists and Calvinism, especially on the issue of election. ?

It is significant that Calvin discusses election in Book 3 of the Institutes under the larger subject of the way we receive the grace of Christ. It does not occur in Book 1, which centers on the nature and character of God. Election must be seen in the context of Calvin’s dealing with how the saving work of Christ becomes operative in a person’s life. Election is not a fatalism that affirms “what will be will be.” ?

At this point, we should recall two central affirmations in Calvin’s thinking. First, God is sovereign in human affairs. He will accomplish His perfect will in human history. His sovereignty is also manifest in individual human lives. From start to finish, salvation is purely an act of God. It is not an achievement which a person earns by his own effort or merit. ?

Second, sin has twisted every aspect of human experience. It has poisoned the heart, mind, body, spirit, and will. Thus, man is incapable of arriving at saving knowledge. Such knowledge can come only by a direct act of a gracious God.

Calvin knew that he was a believer in Jesus Christ. He knew that the gift of life had been given to him. Given the two affirmations above, election became the explanation for why he believed. Taking seriously God’s sovereignty, he realized that what had happened in his life was purely the work of God. Taking seriously the utter brokenness of the human condition, he knew that he was incapable of believing in Jesus within himself. Thus, election became, for him, the way of explaining why he believed.

He looked around and saw others who did not believe. Some in his day scorned and rejected the claims of the gospel as being utter nonsense. Others heard the gospel but found their sinful pleasures to be too much to give up. Why had the gospel brought life to some but not to others? Calvin concluded that some were elected by God to life and others to damnation.

In his discussion, Calvin acknowledges that the whole issue of how Christ’s redemptive work changes human life is mysterious. He says, “Let them remember that when they inquire into predestination they are penetrating the sacred precincts of divine wisdom” (Institutes, Book 3, Ch. 21, Sect. 1). He goes on to warn that “it is not right for man unrestrainedly to search out things that the Lord has willed to be hid in himself, and to unfold from eternity itself the sublimest wisdom, which he would have us revere but not understand that through this also he should fill us with wonder” (Institutes, Book 3, Ch. 21, Sect. 1). ?

Calvin finds the basis of election to be in scripture. He sees it first in God’s choice of Israel to be His covenant people. Such texts as Deuteronomy 4:37, 7:7-8, and 32:8-9 indicate that God chose Israel over the other nations to be His people. His choice of them was not because they were more righteous than others. It was not because they were better than other nations in any way. He chose them solely because He is God. ?

The Old Testament clearly shows, however, that not everyone in Israel obeyed God. The burden of the prophets’ preaching was to call Israel to repentance. The exile and other tragic events show that many failed to heed that call. ?

Thus, Calvin recognizes how the Old Testament shows that God also elected individual Israelites within the nation. Isaac is chosen over Ishmael. Jacob is chosen over Esau. ?

At this point, Calvin anticipates the charge that God is unfair and shows favoritism. He responds, “In the election of a whole nation God has already shown that in his mere generosity he has not been bound by any laws but is free, so that equal apportionment of grace is not to be required of him” (Institutes, Book 3, Ch. 21, Sect. 6). ?

What is present in the Old Testament about Israel, according to Calvin, is even more pronounced in the New Testament about believers. He sees the election of believers in Jesus being set forth in texts like John 6:37, 39, 44-45; 15: 16; Ephesians 1:4-5; and Romans 9-11. In election of believers, God gives one the ability to repent and believe the gospel. Calvin says, “To sum up: by free adoption God marks those whom he will to be his sons; the intrinsic cause of this is in himself, for he is content with his own secret good pleasure” (Institutes, Book 3, Ch. 22, Sect. 7). ?

For some later Calvinists, this doctrine of election became a source of pride and arrogance. Some have justified the possession of wealth and power on the basis of election. Others have used it to discourage missionary work and any attempts at evangelism. All of these notions are foreign to Calvin himself. ?

For Calvin, election points away from oneself and demonstrates the goodness and greatness of God. No one can take any pride in a gift. We can be proud of things we earn but never a gift. Calvin remarks, “The foundation of divine predestination is not in works” (Institutes, Book 3, Ch. 22, Sect. 11). Thus, the elect can never be proud, only humbly acknowledge that God has been gracious. ?

Election does not insure earthly blessings. One is elected by God for the purpose of humbly obeying God’s will. In Calvin’s discussion of the Christian life, he maintains that the sum of the Christian life is to deny ourselves. The purpose of election is so that “a man depart from himself in order that he may apply the whole force of his ability in the service of the Lord” (Institutes, Book 3, Ch. 7, Sect. 1). As in the case of Israel, the believer’s election is for service, not privilege. The assurance that one has been accepted by God allows one to live daringly and boldly in discipleship. ?

Election, according to Calvin, in no way discourages the proclamation of the gospel. To begin with, only God knows who the elect are. Furthermore, Calvin tries to take seriously the statements in scripture which maintain that God calls all people: “I have elsewhere explained how scripture reconciles the two notions that all are called to repentance and faith by outward preaching, yet that the spirit of repentance and faith is not given to all” (Institutes, Book 3, Ch. 22, ?Sect. 10). ?

Election gives glory to God alone. Salvation is His gift given to those who do not deserve it. From start to finish, it is a work of grace. Because of this, all boasting is excluded, and the elect live in quiet trust that their destiny has been settled and lies in the hands of a merciful God. ?

The current controversy among some Baptists over Calvinism is not new. Many historians place the origin of Baptists in the early 1600s in England. Although Baptist beginnings occurred in reaction to a state church and not because of a particular theology, Baptists were Calvinistic in their thinking. The two groups that emerge in the early 17th century – General and Particular Baptists – were divided over how strictly they followed many of the tenets of Calvinism.

The primary point of disagreement between these two groups related to election. Election, or predestination, touches two other points of Calvinism that developed after Calvin’s time. Later Calvinism taught (1) irresistible grace and (2) limited atonement. Since God had chosen who would be saved, the elect could not resist His grace. If Christ’s atoning death was for all (elect and condemned), then its benefits could not be wasted on those who were not among the elect. ?

Calvin arrived at his view of election from scripture. He was a bright and sensitive student of the Bible who wrote commentaries on most of it. For him, the doctrine of election and the above related doctrines were affirmed in scripture. ?

His chief adversary was Jacobus Arminius, already discussed in an earlier article. In responding to Calvin, Arminius assembled a whole array of biblical texts which seemed to affirm human freedom in the ability to choose or reject God’s salvation as well as that Christ had died for all. ?

In any debate over election, this approach is still used. For every text called forth to support election, one is cited that seems to deny it. How is the doctrine of election either supported or denied in scripture? Baptists have always maintained that the Bible alone is the supreme standard for measuring the truthfulness of any religious claims. Creeds, confessions, and even the revered writings of the church’s great theologians are secondary in authority. How are we to read the biblical evidence regarding election?

Before attempting to do so, certain observations should be made. How Christ’s work of redemption changes our sinful lives is the greatest mystery of all. It is proper to seek to understand it. This desire is not sinful. We must be careful, however, not to reduce the mystery of God’s ways to our doctrinal statements. Our most profound theological statements may point to God, but they do not capture Him. It is preposterous for us to say, “God cannot -,” for God is God, and He can do what He desires without either our permission or understanding. Is not this fact illustrated in His use of the pagan Babylonians to bring about the destruction of Jerusalem and the subsequent exile of Israel? Is this not precisely the meaning of the incarnation, when God chose to become flesh in a lowly Palestinian family – in Nazareth of all places? In both instances, God’s actions were not anticipated, were not understood by many, and were resisted by the very people most prepared to accept them. The mystery of God’s dealing with us in salvation will never be removed by our doctrinal statements. Salvation is, first and last, a gift from God. If we are saved, it is because God is gracious and merciful. ?

The biblical texts which support election and those which seem to question it have been studied by able scholars and church leaders. We will not repeat the results of those studies here. Instead, we will turn to Jesus Himself. Jesus talked about the mystery of God’s saving sinful humanity in terms of the Kingdom. He came preaching the coming Kingdom. Obviously, those who heard Him wanted to know what this Kingdom would be like and when it would come. They sought to understand its mystery very much like we do the mystery of God’s salvation. They desired concrete answers to their questions. ?

How did Jesus respond? He used parables, metaphors, and images. He likened the Kingdom to a man who sowed a field (Mark 4:26-29), a man who discovered a buried treasure (Matthew 13:44), and a banquet where people would come from everywhere to feast with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Matthew 8:11). Jesus’ language pointed to certain aspects of the Kingdom, but it never eliminated its mystery. His words were like a flashlight piercing the night and revealing a way to walk in the dark. ?

With these observations in mind, let us look at one event and one image which pierce the darkness of mystery regarding salvation but which do not remove it entirely. John alone records the dramatic encounter between Jesus and Judas Iscariot around the last supper (John 13: 21-30). Most scholars conclude that John affirms God’s election more than the other three gospels.. Calvin himself frequently cites texts from John. ?

In the scene around the table, Jesus announces His betrayal by one of the twelve. The disciples are noticeably disturbed, and ask who it will be. Jesus clearly identifies His betrayer by handing Judas a piece of bread dipped in wine. The meaning of this gesture is clear to anyone knowledgeable about Eastern culture. Jesus was offering Judas a way out. Sharing bread with one’s enemy was an attempt to be reconciled to him. As He stretched forth His hand to Judas, Jesus was saying, in effect, “Judas, you don’t have to do what you’ve chosen to do.” If Judas had accepted Jesus’ offer, he would have received the bread, eaten it, then dipped it in the wine and returned it to Jesus. The text clearly shows that Judas made his choice to betray Jesus. Yet, it is in this passage that John makes a profound statement of election by saying that Satan entered Judas (13: 27). ?

In this story, John holds these two seemingly contradictory truths side by side and does not resolve the tension between them. If we allow this event to shine light on the question of election, we can say clearly that our salvation from start to finish is a work of God alone which will be frustrated by nothing. Yet, at the same time, it is a conscious choice we make. The truth is not in the middle. It is in the extremes, the paradox. The effect of this truth is to allow us to live in quiet trust that our fate lies securely in the hands of a faithful and merciful God. Yet, at the same time, it jolts us from the delusion of glibly presuming upon the grace of God as if we are simply reading lines from a play written by someone else. Any attempt to resolve this mystery in a logical manner leads us away from the paradoxical nature not only of truth but of the very life of Jesus Himself. ?

The image from the teaching of Jesus which may speak to the question of election is perhaps the most mysterious picture He painted. In Luke 15:11-32, He likens God to a father who defies all social customs and norms of what is right and fair. Instead, He shows a picture of a father lavishly forgiving a rebellious son who deserved condemnation. Many conclude that this is Jesus’ most radical and paradoxical picture of God. ?

There is nothing logical, nothing just about what this father does. Instead, here is a picture of God who yearns, who longs for, who seeks out a lost son to bring him home again. Strikingly absent from this image is any apparent concern about whether the right or just thing has been done, whether the son is among the elect, or whether the son really has the ability to choose. What overshadows these issues is the disturbing paradox of lavish, wasteful, extreme, unreasonable, undeserved love. ?

In any discussion of biblical texts about election, one thing must never be forgotten. In the end, our trust is in a Person, not a doctrine. Our lives are saved not by a correct understanding of a biblical text, but by a merciful God who never gives us what we deserve. Hence, regardless of how we choose to describe the mystery of God’s salvation, there can be no pride or arrogance, but only humble gratitude that God’s love really is lavish, wasteful, extreme, unreasonable, and undeserved.

This series of articles has been an attempt to inform Baptists of the basic components of the thinking of John Calvin and, to some extent, the later Calvinism that developed from it. Baptists have always been practically-minded. The obvious question is: So what? What relevance does Calvin’s thinking have on Baptist life? ?

Before attempting to respond, it is important that we put Calvin himself in perspective. Many consider him to be the greatest mind of the Reformation, but we must not forget that he was a mere man. In the end, his theological assertions, like all of ours, come from one who was as broken as the rest of us. Some in the Reformed tradition have been accused of making Calvin the standard by which the Bible is to be interpreted. Baptists would argue for the reverse order. Calvin’s thinking is not the template by which we understand the Bible. The Bible possesses its own authority, and all forms of Calvinism or any other theology must be judged by it. Although we Baptists have our great theologians of the past and present, we have always been careful to use their insights to help us understand the Bible and not to elevate them into places where they have ultimate authority themselves. ?

That being said, it is helpful to look at those parts of Calvin’s thinking which affirm and strengthen some of our central beliefs and practices as Baptists. Baptists share many things in common with Calvin. The first of these would be Calvin’s high view of scripture. Even a casual reading of the Institutes reveals that it is literally soaked with scripture. While some citations arguably are examples of prooftexting, Calvin made a concerted effort to take the words of the Bible seriously. He was a brilliant biblical scholar who wrote masterful commentaries on almost every book of the Bible. His commentaries are still useful for students of scripture today. ?

For Calvin, the Bible was the ultimate witness to God’s revelation to us in Christ. It is the Bible alone that gives the true picture of the human predicament and God’s provision of salvation in Christ. It is scripture which gives concrete guidance in how to live the Christian life. All creeds, confessions of faith, and traditions of the church are to be judged by scripture, and not the other way around. It would be difficult to find anything in Calvin that Baptists would affirm any more wholeheartedly than this. ?

Another prominent theme in Calvin with which Baptists resonate is the work of the Holy Spirit in understanding scripture. For Calvin, the Bible is more than words. It comes alive and empowers us to obedience as the Spirit takes the written words and makes them into living, breathing words. Without the work of the Holy Spirit, the Bible is without power. ?

Baptists have always been a “people of the Book.” Such a reverence for the Bible, however, can easily slide into the worship of a book with no regard for how the Spirit not only inspired the writing of scripture but also continues to use it to quicken the hearts of people. A high view of Scripture can easily become sterile and heartless without the recognition of the Spirit’s continuing work in our hearing and believing the words of the Bible. ?

We Baptists will do well to ponder Calvin’s view of the human condition. Recall that Calvin saw human beings not necessarily as evil and corrupt but as utterly broken and unable to redeem themselves. We live in a day of various forms of self-help and quick fixes to human problems. One has only to peruse the titles of best-seller books or roam the aisles of a drug store in the diet section to see that there exists a huge appetite among us for quick and painless solutions to complex problems. While embracing the biblical idea of human fallenness, it is quite possible for us to yield to the all-too-easy temptation of thinking that the church’s and the world’s problems can be fixed with clever programming and slick worship experiences. In preaching and in counseling with people, it is easy to throw out simplistic platitudes and Bible verses without listening to the deep pain brought about by our human twistedness. It is true that some human problems have simple answers, but most of the really important ones do not. ?

Calvin’s theology reminds us that at our very best, we do not change people’s lives. People are not saved by our teaching, preaching, or evangelism. Sin is so deeply entrenched in all of us that we can only point to God alone who saves. To live in this realization is to live in simple, child-like trust that our fate lies in His hands alone. Calvin’s understanding of the utter twistedness of human beings is a clear warning to those of us in ministry who take ourselves too seriously and who easily equate our minds with the mind of God. Calvin warns us not to put too much stock in our own knowledge, skills, or righteousness, and never to gloat over the failures of others. Whatever goodness or success in ministry that we enjoy is God’s gift to us. ?

While some forms of Calvinism became over-intellectualized in later years, Calvin made central the necessity of disciplined and fruitful Christian living. While so much later debate centered on election and the role of human responsibility in salvation, Calvin’s emphasis throughout his theology is on living the faith in everyday life. For him, the Christian faith was not only something to be believed, but, most importantly, something to be lived. ?

While Baptists have always taken living the Christian life seriously, it is troubling that most churches never see half of those on the membership rolls. Many of us reduce the Christian life either to some kind of conversion experience in the distant past or to being reasonably faithful to the activities of the church. Our everyday lives, however, often are not really distinguishable from anyone else’s. Calvin argues against any such cheap notion of salvation. For him, the reality of one’s salvation is expressed in the life of discipleship, for which there is no substitute. ?

Clearly, the most troubling aspect of Calvin’s theology for many Baptists is his view that those who are saved are those whom God has chosen before the foundation of the world. Many Baptists rightfully question whether such a view allows for any human responsibility. Numerous biblical texts affirm both truths. ?

It is once again important to note that election, for Calvin, is part of the mystery of God’s nature. Furthermore, its purpose is not to promote boastful pride that one is among God’s elect. Instead, it is to give assurance and confidence that one does nothing to earn salvation but to trust in the merciful faithfulness of God. The result of such confidence is humble service to God, which always takes the place of service to other people. ?

We have suggested that the truth about election is in affirming two truths that seem to be opposites. Regarding salvation, we are saved solely by God’s action on our behalf and because we have responded to God’s invitation in Christ. Affirming these two truths also contains a warning to us. There is little difference in the person who stakes his salvation on a decision made by God before the world began and one who stakes it on an emotional experience at a revival or on being baptized at nine years of age. In either case, the proof of one’s salvation is fruitful living. If such living is absent, one has cause to be concerned.

For more Calvinism-related stories, go to our Calvinism page.