Editor’s note: This is the final article in a three-part series on suicide, pastoral burnout, and pastoral termination. On Oct. 9, in light of high rates of suicide and forced terminations among South Carolina pastors, the Executive Board of the South Carolina Baptist Convention created a special committee to research causes contributing to negative health among pastors and to explore ways to help. (To read the other articles in this series, click here.)

South Carolina Baptist churches lead the way in the percentage of terminated pastors and staff. The number reported does not accurately represent the real number, since many forced terminations or instances where ministers leave under pressure are not reported. The actual number is higher.

Ministers who have been forced out of their churches are more likely to experience lower levels of self-esteem, elevated stress, depression and physical health problems.

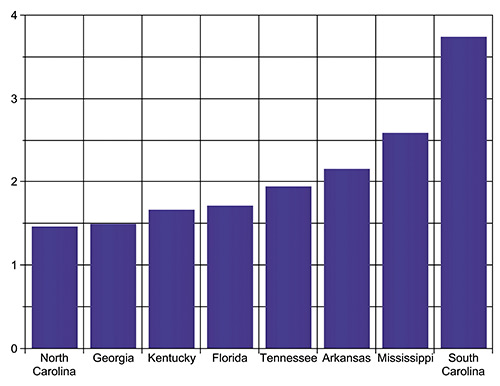

Ministers who have been forced out of their churches are more likely to experience lower levels of self-esteem, elevated stress, depression and physical health problems.When we compare our state with surrounding states, it is easy to visualize our dilemma. The South Carolina Baptist Convention has 2,112 churches; in 2012 we had 79 pastor terminations. North Carolina, with 4,097 churches, had 60 terminations. Georgia has over a thousand more churches than us (3,272) and yet had only 49 dismissals. Tennessee’s 3,037 churches reported 59 terminations.

Why are so many pastors and church staff members forced or pressured to leave their places of service – especially in South Carolina?

Topping the list: control. The issue of who runs the church is the reason given for most pastoral terminations. Other reasons include: conflict that existed within the church before the pastor arrived; members’ resistance to change; the leadership style of the pastor (either too strong or too weak); declining attendance; sexual misconduct involving the pastor; and poor pastoral relationship skills.

The March issue of the Review of Religious Research reported that 28 percent of ministers at some point in their careers had been forced to leave because of personal attacks and criticism from a small faction of the congregation. This corresponds to an article in a 1992 issue of Leadership magazine, where the results of a survey indicated that 43 percent of forced terminations or pressured resignations were caused by a small group of people in the church. According to 71 percent of those surveyed, the faction consisted of 10 people or less.

David Briggs, in “Killing the Clergy Softly: Congregational Conflict, Job Loss, and Depression,” called this small faction of people who pressure a pastor or staff member to leave “clergy killers.” He pictures a dysfunctional church where a small group of members are “so disruptive that no pastor is able to maintain spiritual leadership for long.”

Ministers who have been forced out are more likely to experience lower levels of self-esteem, elevated stress levels, depression and physical health problems. Financial pressure is often present when a minister is forced out. Family tensions are greater following a forced departure. Too often a minister is given little to no severance package. The SCBC recommends “that the church extend a severance package (which should include salary and benefits except business mileage) of at least six months.” The harm inflicted on a pastor’s family can easily leave scars affecting a person’s attitude toward any church for years to come.

Church leaders, staff and pastors can help diffuse a tense situation by becoming better listeners. As the conflict in a church escalates, accusations can easily take the place of effective communication. The purpose of listening is not to agree but to understand. Usually when people feel they have been understood, the disagreement, at least, becomes less destructive.

Church staff members are even more vulnerable than senior pastors. They are dismissed twice as often as senior pastors. Typically, when there is conflict between a staff member and the pastor, the staff member is forced to leave. Rarely is the pastor forced to leave over conflict with a staff member. The possible exception is when a staff member has a much longer tenure than the senior pastor.

Bill Northcott, church-ministry relations specialist with the Tennessee Baptist Convention, has noted, “Conflict damages individuals, the reputation of churches, and the cause of Christ. Lost people are looking for ammunition against the church. Conflicted congregations provide more than enough for lost people to conclude, ‘If that is what being a Christian is about, I don’t need it.’ “

In May, Christianity Today summarized some warning signs for forced terminations:

– A recent church fight.

– Declining attendance.

– The pastor’s sermon lasts between 11 and 20 minutes. (Pastors with shorter sermons are twice as likely to be terminated.)

– Few men in the church. (There is a one in five chance of the pastor being asked to leave when the church numbers around 10 percent men.)

– A woman pastor. (These churches are nearly twice as likely to fire the pastor.)

– A young pastor. (When the pastor is under 30, he is three and a half times more likely to be terminated.)

– An older congregation. (If more than 75 percent of the congregation is over 60, they are three times more likely to dismiss the pastor.)

– A slight majority of the congregation is poor. (Half of congregations where 50 to 74 percent of the members earned less than $25,000 had fired a pastor.)

In 2011, South Carolina led all state Baptist conventions in the South with 3.74 forced pastor terminations for every 100 churches.

In 2011, South Carolina led all state Baptist conventions in the South with 3.74 forced pastor terminations for every 100 churches.Unfortunately, conflict in churches is not uncommon, especially among church leaders. How churches deal with conflict or disagreement is critical in the ongoing spirit and life of the congregation. One psychiatrist who worked with companies that were downsizing concluded that corporations treat their employees better than churches treat theirs. He observed three things in pastoral terminations: The minister was often blindsided; while in shock over this, guilt was dumped on him; and he was then pressured to make a decision.

Even though the problem of pastor and staff termination is growing today, it was also a problem in 1992. Then Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee, former pastor and president of the Arkansas Baptist Convention, said, “Churches are using termination as the ‘weapon of choice’ in targeting church staff problems in epidemic proportions.”

Termination almost always leaves negative outcomes. There are times, however, when it is necessary. How it is done can minimize the negative consequences of the dismissal. Robert Grant works as the director for retirement, insurance and church administration for the South Carolina Baptist Convention. He is a certified mediator and has helped more than 80 conflicted churches, most of them involving the termination of a minister. He offers six suggestions to help avoid a termination:

– Communicate with the pastor early in the dissatisfied situation.

– Use the church bylaws, policies and procedures to reach the best biblical resolution.

– Consider using a mediator from outside the church.

– Avoid any confrontation or emotional discussion during a church business meeting.

– Think about the church’s witness and reputation in the community when considering a dismissal.

– Avoid the trap of using the deacon body in the termination process and consider having a standing personnel committee.

People and families are hurt when a minister is terminated. If a church has a reputation of terminating staff and pastors, it almost always develops the reputation of a “troubled” church. When pastors or staff members have been terminated, it often puts them in the position of being “questionable” in regard to future service.

In South Carolina, our termination rate is high. It is time we gave prayerful and serious thought to our mission to make disciples and realize that a lost world will not give us a hearing if our message is eclipsed by bad behavior and destructive relationships.