My father, a family doctor in my hometown of Manning, S.C., strived to provide excellent medical care to a very impoverished community. He loved what he did.

Nevertheless, in 1965 he left a growing family medicine practice to volunteer for the Air Force in the midst of the Vietnam conflict. Trained as an air surgeon and air commando with the 1st Air Commando Wing, he attended jungle and sea survival schools at England Air Force Base in Louisiana. Upon arrival in Vietnam, he immediately volunteered to work with an outfit called Air America, a CIA undercover organization that sent him and a French-trained Laotian surgeon to Laos posing as missionaries. Since Laos was off-limits to the American military, he had to divest himself of any affiliation with the American armed forces. All of this was top secret for 10 years after the war was over.

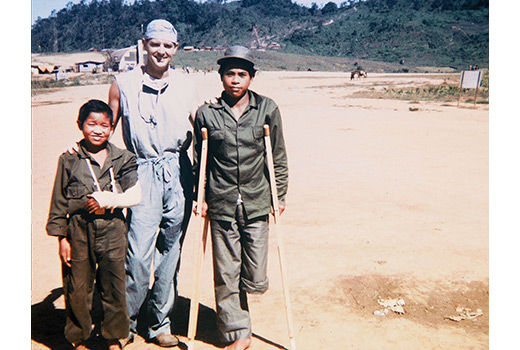

Together, they ran a 100-bed hospital caring for wounded and sick civilians. They conducted four or five major trauma surgeries per day on civilians wounded by gunshots and/or land mines. However, the real reason for their being located on a mountaintop with an airstrip was to care for downed and wounded American airmen, who were airlifted to the hospital, stabilized, then flown farther south to military bases with hospitals. They flew goodwill missions by helicopter to surrounding villages where they set up clinics in the village square, providing modern medical/surgical care to mountain people far removed from access to such care. The chieftains of the surrounding villages came to love my dad, and he loved them as well. He learned their language a bit and spoke it in our home for years afterward. My missionary doctor/air commando/goodwill ambassador father taught me how he loved his mission and how he loved the Laotian people.

The clinic buildings were made of bamboo raised three feet off the ground to avoid the mud created by the monsoon season. The nurses were local Laotian women that he trained in sterile technique. Their water came from a mountain stream down a bamboo pipe, through a gauze pad to strain out the sand, then boiled to sterilize it. The blood bank was a small refrigerator run by a gas generator. Every two to three weeks, he would fly south to one of the air bases, check dog tags until he found the blood types that he needed, then order the unfortunate soldiers to lie on the grass while his corpsman drew blood for his rudimentary blood bank.

Unfortunately, after his second tour he caught falciparum (cerebral) malaria and slipped into a coma for two weeks. Having lost 40 pounds, he nearly died while he was diligently cared for by Air Force physicians in a Philippine hospital. After ultimately recovering, he then requested reassignment to Laos, but the Air Force physicians felt it was too dangerous. Another bout of malaria could have proven fatal since there was no good treatment for that type of malaria in the 1960s. Unfortunately, their little hospital was overrun by the Viet Cong some later, was burned to the ground, and everyone at the hospital was killed.

He was highly decorated for his exploits in Vietnam. One such exploit occurred when his corpsman was shot in the chest standing in the doorway of their surgery center. Dad caught him before he fell to the floor, lifted him to a surgical table, and immediately covered a large sucking wound in his chest. He started IV fluids, inserted a chest tube, administered blood, and held the patient’s hand all the way as he was airlifted to a military base in the South. His corpsman survived, and my dad was awarded a medal for that accomplishment — but, in reality, it was no different from what he did every day in his surgical clinic for the Laotian people.

One can understand why my dad always stood ramrod straight at the playing of the national anthem, why he called to thank World War II veterans for their service on Memorial Day, and why he despised draft dodgers. He loved America, the military, and the flag that represented them both. Should we not be thankful for those who have gone before us, who purchased freedom for us and for those around the world at great risk and great price? This Independence Day, remember our Founding Fathers and every military man/woman since them who has served to preserve, protect and defend all that America stands for here and around the world.

Dad, we remember you fondly. You are still our hero. We speak of you with glowing pride.

— Robert Jackson is a family practice physician in Chesnee.