Thirty years after the Southern Baptist Convention Peace Committee delivered its major report to the convention, Baptists hold a range of views on the committee’s significance.

Some claim it played a positive role in advancing the SBC’s Conservative Resurgence. Others say it helped calm the denominational conflict. Still others have called it a public relations scheme to appease moderates while theological conservatives solidified their control of the convention’s committees and boards.

For all the differences of opinion, Peace Committee members tend to agree the committee was both historically significant and an occasion for camaraderie.

Peace Committee member John Sullivan, former executive director of the Florida Baptist Convention, said the committee included “the best crop of Southern Baptist leadership that existed at that time.”

While “egos were real big,” Sullivan told Baptist Press, “the leadership qualities came out when they needed to” and members “had the privilege of hearing what [one another] had to say from their theological vantage points.”

Formed in 1985 in response to a motion at the SBC annual meeting, the committee was charged with “seek[ing] to determine the sources of the controversies in our Convention, and mak[ing] findings and recommendations regarding these controversies.” Since 1979, theological conservatives had been attempting to gain control of the SBC’s committees and trustee boards.

Initially, the 22-member committee had no official name, but it adopted the name SBC Peace Committee at its first meeting in August 1985. Its members included six men who had served as SBC president or went on to hold the office: Jim Henry, Herschel Hobbs, Adrian Rogers, Charles Stanley, Jerry Vines and Ed Young.

Three other members were nominated for SBC president at some point: Sullivan, Daniel Vestal and Winfred Moore. Another member, Jodi Chapman, was married to future SBC president Morris H. Chapman.

By design, the Peace Committee’s membership included some of the most conservative individuals in the SBC, some of the most leftward-leaning and some in between.

After 14 meetings over two years, the committee reported at the 1987 SBC annual meeting in St. Louis that “the primary source of the controversy in the Southern Baptist Convention is the Bible; more specifically, the ways in which the Bible is viewed.” “Political activities,” the Peace Committee stated, were a secondary factor in the conflict.

Peace Committee recommendations adopted by messengers included affirmation of a “high view of Scripture” as one of the “parameters for cooperation” within the convention and a request that “all organized political factions … discontinue the organized political activity.”

The committee voted to disband in 1988 following a final report to the convention that year.

‘The primary difference’

Vines, former pastor of First Baptist Church in Jacksonville, Fla., said the committee’s most significant accomplishment was helping the SBC’s seminaries move toward affirmation of the Bible’s inerrancy — the belief Scripture is completely true in everything it asserts.

“The primary difference [the Peace Committee] made was that all of our seminaries now have faculties that endorse the inerrancy of Scripture,” Vines told BP.

The committee found that was not the case 30 years ago.

When a subcommittee visited Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in 1986, they were told no one on the Old Testament faculty believed the Bible was inerrant, according to Henry’s autobiography “Son of a Gunn.” At Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, president Roy Honeycutt told a separate subcommittee that professors had taught since at least the 1940s that Adam and Eve might not be historical persons, according to Sherman’s memoir “By My Own Reckoning.”

The Peace Committee also noted a Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary professor who was accused of teaching universalism, the belief all people eventually will be saved. That professor was asked by the administration not to return, though Midwestern president Milton Ferguson said the professor in question fit under the SBC “umbrella,” according to a 2008 doctoral dissertation by North Carolina pastor Marty Jacumin.

During a May 1986 meeting, Hobbs claimed, “We have in our seminaries more teaching and knowledge of [neoorthodox theologian Rudolf] Bultmann than we do Baptist history, and we must work back to the basic Baptist principles and the Baptist Faith and Message,” according to Jacumin’s transcript of a meeting recording.

To remedy the perceived theological drift in seminaries, the committee recommended all convention entities “build their professional staffs and faculties from those who clearly reflect such dominant convictions and beliefs held by Southern Baptists at large.” Messengers adopted that recommendation.

The “overwhelming viewpoint” of Southern Baptists, Vines said, “was that the Bible was without error.” A majority of Peace Committee members “just felt like our institutions ought to reflect the viewpoint of the constituents.”

‘Buying time’

To Sherman, who argued against inerrancy in Peace Committee meetings and in print, the committee was destined not to achieve meaningful peace.

“Most Southern Baptists thought the Peace Committee was working toward reconciliation; in fact, we were buying time for the Fundamentalist takeover to get past a point of no return,” Sherman, who died in 2010, wrote. Only moderates were “willing to do the things that make for peace … . The winners drove the losers out.”

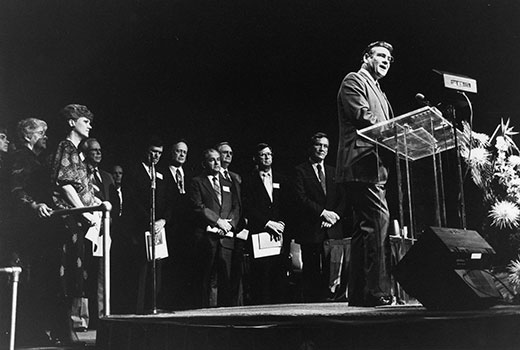

The SBC Peace Committee gathered in October 1986 at the Glorieta Baptist Conference Center with convention entity heads for a meeting and prayer retreat. (Photo by Jim Veneman)

Eventually, Sherman grew frustrated with the committee and resigned after a year of service. Among his frustrations were objections to the so-called Glorieta Statement, a 1986 document issued by the six seminary presidents which declared the Bible “fully inspired” and “not errant in any area of reality.”

Sherman, then pastor of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, wrote that the statement “reeked with words designed to appease” conservatives though the presidents “knew what they had written was not so.”

Despite Sherman’s allegations, Midwestern president Milton Ferguson told the committee, “There is no intent in the document to use slippery language or to try to convey or connote an impression or a feeling that is misleading for public relations purposes,” according to a 1986 recording.

Subsequent discussion suggested Rogers, like Sherman, wondered whether the presidents had conveyed their true sentiments about the Bible.

Sherman’s frustrations also stemmed from being “accused of not believing the Bible” by fellow committee members and being called “liberal” repeatedly, he wrote.

“If the Peace Committee had never met,” Sherman wrote, “the SBC would be exactly as it is today.”

‘Preventing … a split’

For their parts, Sullivan and Henry believe the Peace Committee did, in fact, make the convention more peaceful.

Sullivan, a Louisiana pastor during his Peace Committee service, said the committee’s work likely helped make the final years of the Conservative Resurgence less bitter even if it didn’t change the outcome.

The Peace Committee “slowed down the tension. It abated the tension some,” Sullivan said. “… We realized we didn’t have to get blood on our swords to make changes.”

Henry wrote that “in the long run, I believe [the Peace Committee] succeeded in preventing a major split in our denomination.”

The committee’s meetings — one of which lasted until nearly 4 a.m. — at least built camaraderie among members who did not share the same perspective on the SBC conflict. Vines recalled building friendships with Vestal and pastor-theologian William Hull. Henry “built relationships with everyone,” Sullivan said.

In recordings, all members seemed to treat Hobbs with deference and respect as an elder statesman in Baptist life, even when they disagreed with him. Jodi Chapman told BP she enjoyed Hobbs’ sense of humor and “had a great time” with him. He died in 1995.

‘Willing to sacrifice’

After three decades, Vines hopes Southern Baptists will appreciate the service of every Peace Committee member and take particular note of the sacrifice some members made.

“I would want Southern Baptists to know that there was a group of us who were willing to sacrifice … whatever necessary to return Southern Baptists to their conservative roots,” Vines said. “I’m sure we made mistakes along the way. But I believe with all my heart that our intentions and desires were noble.”

— David Roach is chief national correspondent for Baptist Press, the Southern Baptist Convention’s news service.