It was October 1966, and Earl Lewers was behind the wheel of his pride and joy: a newly purchased 1967 Buick Wildcat, an emerald-green beauty with 360 restless horses under the hood.

Then came the accident, and Lewers found himself sitting in a “beat-up” car on the side of Mauldin Road, where he heard a familiar voice, as if from within him, speak: “Earl, you never will do no good until you obey.”

Lewers tried to ignore the voice, as he had many times before. But later that day, when he pulled into the parking lot of his home church, Reedy River Missionary Baptist Church in Greenville, he suddenly knew he could ignore the persistent voice no more. “I drove up on the yard, and I accepted,” he said. “God just wouldn’t leave me alone, so I accepted the call right there.”

It was the first day of a 42-year ministerial journey that concluded in October 2008 when Lewers, 69, retired as pastor of Open Heart Baptist Church, a small neighborhood church in the Dunean section of Greenville.

Along the journey, a sometimes difficult one in which he felt cut off from his fellow black pastors, Lewers learned to trust that God would “make a way somehow.”

He grew up in Mauldin, the fourth of six children — three boys and three girls. His mother died when he was 5, and his father, with the assistance of a great aunt, raised the children.

At Sterling High School and later at Bryson High, the students and faculty predicted that young Lewers was bound for the ministry. Lewers had other ideas. After graduating in 1957, he set out to earn money and make a life of his own, which including getting married and starting a family. It would be 10 years and five children later before he found himself sitting in the parking lot of his church, finally saying yes to God’s claim on his life.

Lewers said his pastor, the late S.C. Cureton, offered some simple if disquieting advice: “If you are going to preach, you have to go to school. I won’t have a jackleg coming up under me.”

“There I was — five children, a house, and now a new automobile — and he’s saying you must quit your job and go to school. It was crazy. I don’t know how I did it, but I quit my job and went to school. Don’t ask me how I made it, but I made it.”

Finances were tight for the Lewers family, but “through friends and all, I was able to make it,” he said. One who helped out was Lewers’ father, who stepped in to help his son keep his prized Buick Wildcat.

For three and a half years, Lewers attended Morris College, a historically black school in Sumter. He was on campus the terrible night when news began to spread that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. The events surrounding King’s death awakened Lewers (who knew from personal experience what it was like to go to the back door of a restaurant for service) to the stark realities of the civil rights movement. “That’s when it really hit me, when the one who was bold enough to stand up to let the world know, was gone,” he said. “That’s when I began to deal with it.”

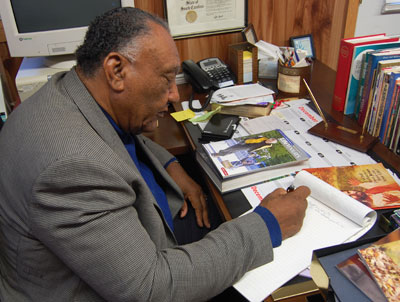

Lewers at the desk of his study.

“Of course, I was also one who believed in Christianity, in trusting God. And I believe that God called us for a different purpose. I think God called leaders for civil rights, and he called ministers and leaders to be Christian leaders. That’s where I draw the difference: You can be a civil rights leader without being a Christian, but you can’t be a Christian without being a good citizen.”

Lewers left Morris College in 1970 and began pastoring churches. He served two churches simultaneously in Chester and later was pastor of two churches in Greenville County.

In July 1977, he responded to a call to be pastor of a group of people who wanted to start a church on the south side of Greenville. The church met for several months at the Watkins-Garrett-Wood Mortuary. Then, in 1978, the congregation bought the old Franklin Baptist Church building on Stafford Street, and Open Heart Baptist Church had a home.

Lewers led Open Heart to join the Greenville Baptist Association. Open Heart was the first historically black church to become a member of the group of cooperating Southern Baptist churches. Lewers said he believed Southern Baptists had a good educational program, “and I was wanting the educational program for the congregation.”

He hoped to share the educational program with his friends. What he discovered when he tried to talk with them about it, however, surprised and disappointed him. “I didn’t have any problem with white churches,” he said, “but I was really hurt over my black brothers, because I was isolated. I was just isolated out there. To many, I still am.”

“Thank God for Greenville Baptist Association and the state convention. None of them let me down, and they used me to work in so many different ways.” In 2000, Lewers was elected moderator for Greenville Association, becoming the first black pastor to hold the position within the South Carolina Baptist Convention.

Lewers has now been retired for two months and jokes that the only thing he misses is his paycheck. He hopes area churches, both black and white, will offer him the opportunity to do some supply preaching. “If I can preach a couple of Sundays a month, I’ll be happy,” he said.

He and his wife, Ruby, a retired school teacher, still live in the church parsonage, a gift from the Open Heart congregation, for as long as they wish to stay. Behind the parsonage is a small study in a storage building outfitted with paneling and carpet and a wall heater/air conditioner. It’s in his cozy office that Lewers prepares sermons, or watches TV on the small flatscreen his children gave him for Christmas, or sits and talks with friends — which he admits is his favorite thing to do. “I don’t isolate against no one,” he said.

Just beyond Lewers’ office building is an old garage. Behind the double doors sits a meticulously maintained ’67 Buick Wildcat, a 42-year-old emerald-green beauty with 360 horses under the hood, a rumbling reminder of a dad who rescued his son’s car … and a son who answered his Father’s call.