It has become almost traditional that Loyd Melton, professor of New Testament at Erskine Seminary, lead the Winter Bible Study in late January at Earle Street Baptist Church in Greenville.

Kirkland

KirklandOn Jan. 23, he came to Earle Street for the fifth time to teach Paul’s letter to the church at Colossae, preaching different sermons at the two worship services and giving lectures during the Sunday school hour and in the afternoon following a soup lunch served by the church.

This year’s visit was more deeply moving for both the preacher-teacher and the congregation, because Melton, widely known among South Carolina Baptists who have studied under him at Erskine, had been seriously ill for months, though he now is recovering. We at Earle Street were not certain he would be up to the task of teaching the Bible study and at times he probably was not sure either.

He was, however, the Melton that we and countless others have known him to be. A former Baptist pastor in South Carolina with a Ph.D. from Southern Seminary, he is a favorite at Earle Street, loved for the warmth of his spirit, eagerly heard for the richness of the content of his sermons and lectures, and appreciated all the more for the simplicity and clarity of language in his presentations.

Melton holds the John Montgomery Bell chair in New Testament studies and directs the seminary’s doctor of ministry program. At Earle Street, he preached and lectured in his usual manner, with no notes at hand, but with his Greek New Testament ever in hand.

He said it was not much different from now when Paul wrote to the fellowship at Colossae to set straight misconceptions of Jesus that were prevalent among the “free thinkers” in the Lycus Valley where the church founded by Epaphras was located.

“Every generation,” he said, “is confronted by this man, Jesus of Nazareth, and must decide what to do with him. The more common response is to fashion him into a Jesus who fits that particular time and place. What we believe about Jesus determines how we conduct our lives.”

Calling attention to the apostle Paul’s own characterization of Jesus as “the visible likeness of the invisible God,” Melton said simply, “When you see Jesus, you see God.”

The “great stumbling block” for believers today he emphasized, “is not in the confession of our faith, but living it,” which he said calls for a “radical renunciation of ourselves” in order to flesh out in daily living what is elementary to Christianity: “It’s about Jesus,” he said, “it’s not about you and me.”

The Erskine professor challenged his audience to take the life given to them by God through Christ and “pour it out into the world in which he has placed us. Life is about giving back, about pouring out.”

If my mind ever wandered even momentarily during Melton’s presentation at Earle Street, it was only to allow myself to be taken back in memory to the classroom where I heard and absorbed the same New Testament truths as a seminarian taught by the same man in the same manner – scholarly, but simply.

I was an older student at Erskine, in my early 50s when I received my master’s degree there. I remember as if it were this morning the day I took my schedule of classes and their teachers to seminary dean Randy Ruble for approval as I prepared for my first semester at the Due West school.

As he examined my proposed courses and professors, he smiled, looked up at me and pointed to the name I would come to revere – and perhaps fear, too, for a time: Loyd Melton. “You,” Ruble told me with no doubt in his mind, “will become a disciple of his.” By definition, I certainly would be a disciple – a learner studying under a teacher. But I sensed even then that the dean’s evaluation of my future relationship with Melton would grow beyond the general definition of a disciple as simply “a learner.” And he would be right. Surprised but pleased by Ruble’s remark to me, I asked, “Is Dr. Melton really that good?” He answered without any hesitancy, “Yes, Don, he’s that good.”

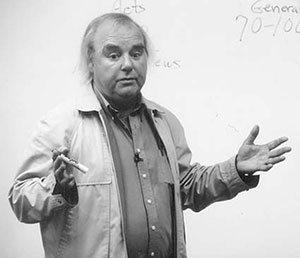

Loyd Melton in the classroom.

Loyd Melton in the classroom.I flowered under his instruction both spiritually and intellectually and walked willingly through doors of thinking that he opened for me to find reaffirmation after reaffirmation of a faith, now expanded, that was deeper, wider and more wonderful than my previously limited notions about my Christ.

As my class in New Testament exegesis drew to a close one semester, I submitted to him my final paper and hoped for the best. He later returned it to me with a personal note included. He praised my writing for its “precision and gentleness” and noted at the end, “Call me Loyd, if you will.”

Though we are friends, I do not recall ever – whether I am talking about him or speaking to him – calling him Loyd. And probably I never will because of the great respect I have for him as my teacher, whose influence in my life did not end when I graduated from Erskine Seminary. Today, I am still a disciple of his. It is a title I bear proudly, but mostly humbly.